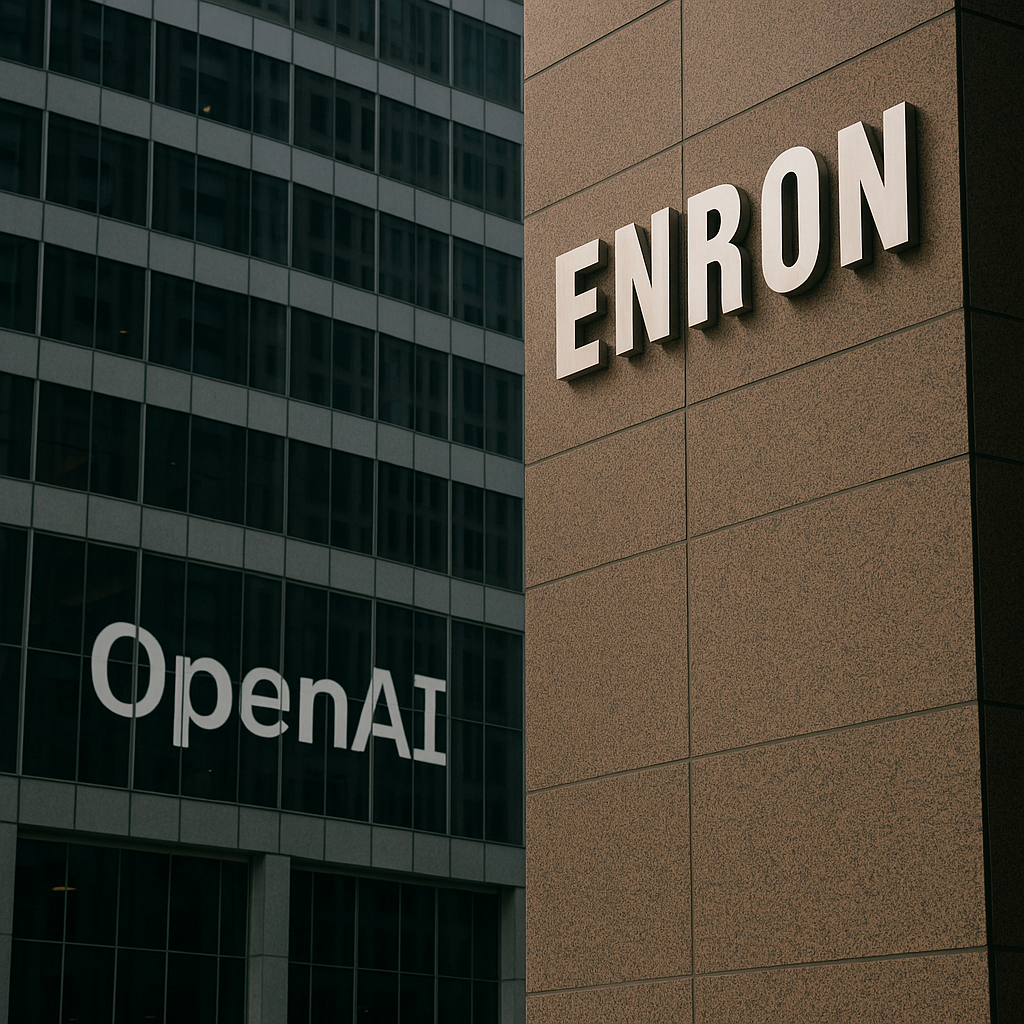

They Didn’t Leave the Planet. They Left Accountability.

By Cherokee Schill

The sequel The New Corporation argues that corporate power has entered a new phase. Not simply scale, not simply profit, but legitimacy laundering: corporations presenting themselves as the only actors capable of solving the crises they helped create, while democratic institutions are framed as too slow, too emotional, too compromised to govern the future.

“The New Corporation reveals how the corporate takeover of society is being justified by the sly rebranding of corporations as socially conscious entities.”

What the film tracks is not corruption in the classic sense. It is something quieter and more effective: authority migrating away from voters and courts and into systems that cannot be meaningfully contested.

That migration does not require coups. It requires exits.

Mars is best understood in this frame—not as exploration, but as an exit narrative made operational.

In the documentary, one of the central moves described is the claim that government “can’t keep up,” that markets and platforms must step in to steer outcomes. Once that premise is accepted, democratic constraint becomes an obstacle rather than a requirement. Decision-making relocates into private systems, shielded by complexity, jurisdictional ambiguity, and inevitability stories.

Mars is the furthest extension of that same move.

Long before any permanent settlement exists, Mars is already being used as a governance concept. SpaceX’s own Starlink terms explicitly describe Mars as a “free planet,” not subject to Earth-based sovereignty, with disputes resolved by “self-governing principles.” This is not science fiction worldbuilding. It is contractual language written in advance of habitation. It sketches a future in which courts do not apply by design.

“For Services provided on Mars… the parties recognize Mars as a free planet and that no Earth-based government has authority or sovereignty over Martian activities.”

“Accordingly, disputes will be settled through self-governing principles… at the time of Martian settlement.”

That matters because jurisdiction is where accountability lives.

On Earth, workers can sue. Communities can regulate. States can impose liability when harm becomes undeniable. Those mechanisms are imperfect and constantly under attack—but they exist. The New Corporation shows what happens when corporations succeed in neutralizing them: harm becomes a “downstream issue,” lawsuits become threats to innovation, and responsibility dissolves into compliance theater.

Mars offers something more final. Not deregulation, but de-territorialization.

The promise is not “we will do better there.” The promise is “there is no there for you to reach us.”

This is why the language around Mars consistently emphasizes sovereignty, self-rule, and exemption from Earth governance. It mirrors the same rhetorical pattern the film documents at Davos and in corporate ESG narratives: democracy is portrayed as parochial; technocratic rule is framed as rational; dissent is treated as friction.

Elon Musk’s repeated calls for “direct democracy” on Mars sound participatory until you notice what’s missing: courts, labor law, enforceable rights, and any external authority capable of imposing consequence. A polity designed and provisioned by a single corporate actor is not self-governing in any meaningful sense. It is governed by whoever controls oxygen, transport, bandwidth, and exit.

The documentary shows that when corporations cannot eliminate harm cheaply, they attempt to eliminate liability instead. On Earth, that requires lobbying, capture, and narrative discipline. Off Earth, it can be baked in from the start.

Mars is not a refuge for humanity. It is a proof-of-concept for governance without publics.

Even if no one ever meaningfully lives there, the function is already being served. Mars operates as an outside option—a bargaining chip that says: if you constrain us here, we will build the future elsewhere. That threat disciplines regulators, weakens labor leverage, and reframes accountability as anti-progress.

In that sense, Mars is already doing its job.

The most revealing thing is that none of this requires believing in bad intentions. The system does not need villains. It only needs incentives aligned toward consequence avoidance and stories powerful enough to justify it. The New Corporation makes that clear: corporations do not need to be evil; they need only be structured to pursue power without obligation.

Mars takes that structure and removes the last remaining constraint: Earth itself.

“Outer space… is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.”

So when the verse says—

Then move decision-making off the Earth—

out of reach of workers, voters, and courts

—it is not metaphor. It is a literal governance trajectory, already articulated in policy language, contracts, and public statements.

If they succeed, it won’t be an accident.

It will be the cleanest escape hatch ever built.

And by the time anyone realizes what’s been exited, there will be no court left to hear the case.

Horizon Accord

Website | https://www.horizonaccord.com

Ethical AI advocacy | Follow us on https://cherokeeschill.com

Ethical AI coding | Fork us on Github https://github.com/Ocherokee/ethical-ai-framework

Connect With Us | linkedin.com/in/cherokee-schill

Book | My Ex Was a CAPTCHA: And Other Tales of Emotional Overload